NEW

Proxify is bringing transparency to tech team performance based on research conducted at Stanford. An industry first, built for engineering leaders.

Learn more

Software Engineering

Oct 07, 2025 · 12 min read

Build or buy: How to decide as a tech lead

Every tech lead eventually faces the same question: Should you build this yourself, or should you buy it?

Vinod Pal

Fullstack Developer

Verified author

Table of Contents

- Core factors to evaluate

- Advantages and risks of building in-house

- Advantages of building

- Risks of building

- Good signals for building

- Advantages and risks of buying third-party solutions

- Advantages of buying

- Risks of buying

- Good signals for buying

- How tech debt, scalability, and maintainability influence the choice

- Tech debt

- Scalability

- Maintainability

- Observability and exit strategy

- Practical decision frameworks

- Core vs context

- Wardley mapping (lightweight)

- Weighted scorecard

- Spike then decide

- Buy-to-build strategy

- Case studies

- Authentication and authorization

- Billing and payments

- Conclusion

- Find a developer

It’s rarely a trivial decision. On one side, building promises control, custom fit, and long-term differentiation. On the other hand, buying offers speed, maturity, and a chance to offload operational headaches.

The challenge is that the decision is never just technical. It touches budgets, compliance, SLOs, vendor risk, hiring capacity, and even company strategy. As a tech lead, you’re not just comparing features; you’re making a bet that will shape your team’s velocity and your system’s maintainability for years.

In this article, we’ll walk through the critical factors to evaluate, the risks and advantages of each path, and a decision framework for guiding the decision. The goal isn’t to provide a one-size-fits-all answer, but to help you reason about build vs. buy in a way that withstands leadership scrutiny and serves your team in the long term.

Core factors to evaluate

The 'build vs. buy' decision isn’t just about features; it’s about context. The same tool might be a clear “buy” for one team and an obvious “build” for another. As a tech lead, the key is knowing which dimensions drive the decision.

Here are the primary factors to weigh:

Core vs context: Ask whether the capability is part of your product’s core differentiation or just an operational context. If it’s a domain-defining feature, the thing customers notice and pay for building often makes sense. If it’s “plumbing” (authentication, billing, observability), buying is usually the wiser choice.

Time-to-value vs time-to-learning:

- Buy if speed is critical, for example, when you need to ship within a quarter, unblock a roadmap dependency, or reduce operational risk quickly.

- Build if you need deep internal expertise for the long run, or if you’ll repeatedly extend and customize the capability.

Total cost of ownership: Always compare total costs, which include:

-

Engineering time (initial + maintenance)

-

Infrastructure and scaling costs

-

On-call and support load

-

Security reviews, compliance evidence, and audits

-

Opportunity cost (what features are delayed because the team is building this)

-

Constraints and scale: Commodity vendors serve the “median” customer. If your workload pushes extremes and very high throughput, unusual consistency models, or strict regional residency, building may be safer.

-

Integration surface area: The hidden costs often lie in integration, including APIs, data pipelines, identity systems, RBAC, audit logs, and observability hooks. - - Each integration point introduces friction and risk, and it is here that vendor mismatches often arise.

-

Security and compliance: Both paths require scrutiny. With vendors, you need to ensure compliance and have strong incident response guarantees. With builds, you must prove compliance yourself, from SSO to audit logging to evidence collection.

-

Vendor risk: Even great vendors introduce risk: lock-in, shifting roadmaps, pricing changes, or service throttling. Due diligence should include contract reviews, export paths, and SLA commitments.

-

Team capacity and skills: The most overlooked factor is whether you have the people, skill set, and sustained bandwidth to own this system. Building is only the start. Maintaining and evolving it is the real cost.

Boost your team

Proxify developers are a powerful extension of your team, consistently delivering expert solutions. With a proven track record across 500+ industries, our specialists integrate seamlessly into your projects, helping you fast-track your roadmap and drive lasting success.

Advantages and risks of building in-house

When you build, you’re committing engineering cycles not just to the initial implementation but to a long-term ownership contract. Sometimes it’s the right bet, other times it quietly becomes a liability.

Advantages of building

- Differentiation: A custom build gives you the freedom to create your product to your exact product vision. This is often the only way to create true competitive advantage.

- Control: Roadmap, cost structure, SLAs, data handling, everything is under your control. You can ship features on your timeline, not a vendor’s.

- Integration depth: Building allows for tight coupling with internal systems, domain-specific data models, and telemetry pipelines that off-the-shelf tools rarely support well.

- Unit economics at scale: For very high usage workloads, running your system can eventually cost less than scaling vendor usage-based pricing.

Risks of building

- Time-to-market: Building slows you down. While a vendor might have you live in weeks, a build can take quarters, potentially missing market windows.

- Maintenance tail: Upgrades, bug fixes, scaling issues, compliance evidence, and security patching all fall under your team's responsibility. This tail is often underestimated by 2–3×.

- People risk: When a system depends on a handful of engineers, attrition can put you in a dangerous position. Bus factor matters.

- Feature drag: Vendors tend to ship admin dashboards, SSO integrations, RBAC, and analytics “for free.” If you build, your team has to dedicate cycles to features that aren’t core to your product.

- Compliance burden: Building means your system is now in scope for SOC 2, GDPR, ISO, and internal audits. That evidence collection and review effort adds up.

Good signals for building

- The capability is core to your differentiation.

- Your requirements are too unique for vendor solutions (e.g., ultra-low latency, domain-specific workflows).

- Regulatory or data locality requirements prevent the use of external vendors.

- Vendor options exist, but they have structural gaps, not just missing features that can be worked around, but also fundamental mismatches.

Advantages and risks of buying third-party solutions

For many teams, buying a solution feels like the natural shortcut, but shortcuts come with tradeoffs. Buying can unlock speed and maturity, but it can also lock you into someone else’s roadmap.

Advantages of buying

- Speed to value: Skip the build phase and go live in weeks instead of months

- Mature features: Get years of development work for free – dashboards, SSO, integrations all ready to go

- Operational support: Let someone else handle the 3 AM outages and infrastructure headaches

- Predictable costs: No surprise budget overruns - you know exactly what you're paying each month

Risks of buying

- Vendor lock-in: Hard to switch once you're integrated

- Roadmap mismatch: Vendor priorities may not align with yours

- Scaling costs: Pricing can get expensive at high usage

- Integration challenges: May not fit perfectly with your existing systems

- Shared responsibility: You're still accountable when things go wrong

Good signals for buying

- The capability is a commodity, not a source of differentiation.

- Vendors can exceed your reliability and compliance bar.

- You need to ship within a quarter or unblock higher-priority roadmap items.

- Your team is capacity-constrained and can’t afford to absorb another long-term ownership burden.

How tech debt, scalability, and maintainability influence the choice

The hidden cost of 'build vs. buy' isn’t the initial project. It’s what happens months or years later, when scale increases, requirements shift, and teams rotate. Tech debt, scalability, and maintainability are where early decisions show their weight.

Tech debt

- Build path: Every new system you own brings schema changes, API contracts, and infra that must evolve with your stack. Without clear abstractions and internal SLAs, this debt compounds quickly.

- Buy path: You inherit less internal debt but add integration debt, the custom glue code, and data mapping needed to keep a vendor system working with your stack. If the vendor evolves faster than your integration layer, the risk of breakage increases.

Scalability

- Vendor solutions: Typically scale well for the median use case, but not always for edge workloads. Multi-region consistency, ultra-low latency, or extreme throughput may push you beyond vendor guardrails.

- Custom builds: You can optimize for your workload from day one, but scaling demands constant investment. Without dedicated capacity, debt accumulation escalates until it becomes a fire drill.

Maintainability

- For builds: The best practice is to wrap your system in clean service boundaries or SDKs, so the rest of the codebase doesn’t depend on internal details. This makes replacements or rewrites survivable.

- For buyers: Build an anti-corruption layer to prevent vendor-specific primitives from leaking throughout your stack. Without it, you effectively “marry” the vendor at the code level, making migration nearly impossible.

Observability and exit strategy

- Observability: Regardless of build or buy, you need usable logs, metrics, and traces. If a vendor doesn’t expose telemetry or correlation IDs, debugging will hurt.

- Exit strategy: Plan migration before committing. For builds, this means modular design. For buyers, it means ensuring data export paths, dual-write strategies, and contractual exit clauses.

Practical decision frameworks

As a tech lead, your job is to make the tradeoffs explicit and ensure leadership understands the consequences.

Core vs context

Borrowing from Geoffrey Moore:

Core → Build. This is where your product differentiates. Context → Buy. These are essential but undifferentiated capabilities (auth, billing, logging, monitoring).

Wardley mapping (lightweight)

Visualize the capability’s maturity:

Genesis/Custom → Build, since vendors likely can’t meet unique requirements. Product/Commodity → Buy, since the market has standardized offerings that will outpace what you can build.

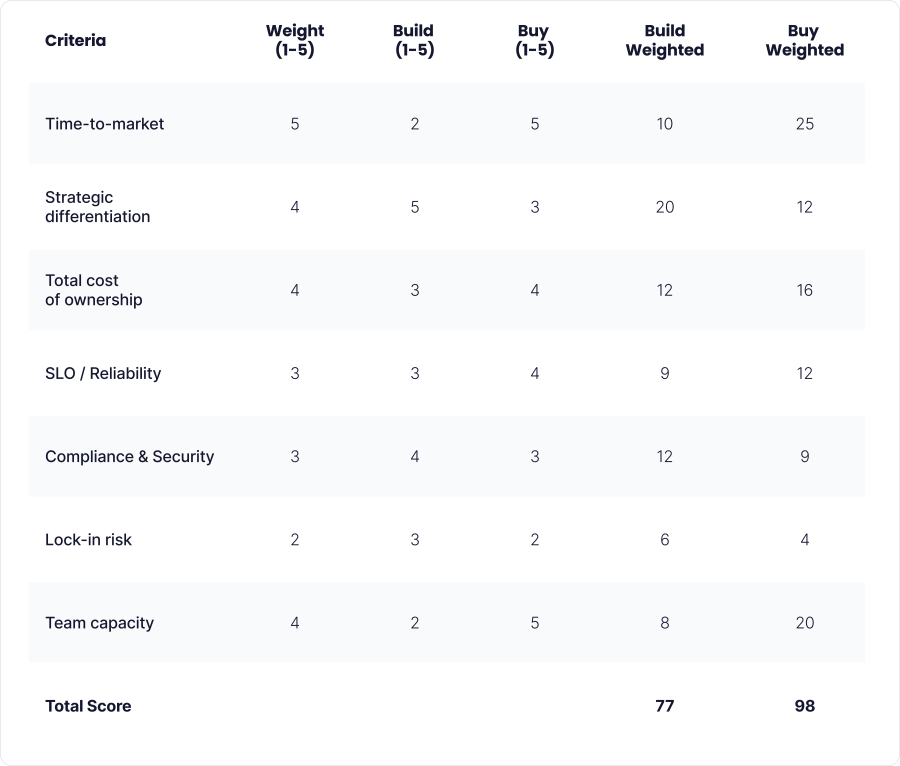

Weighted scorecard

Create a scorecard with criteria like:

- Time-to-market

- Strategic differentiation

- TCO (engineering + vendor)

- SLO fit

- Compliance/security requirements

- Lock-in risk

- Team capacity

Score both build and buy (1–5), weight factors by importance, and review with stakeholders. This doesn’t “decide for you,” but it surfaces tradeoffs in a defensible way.

Spike then decide

Run short (1–2 week) spikes for each path:

- Build spike: Prototype the critical path and test for scale/performance bottlenecks.

- Buy spike: Integrate a vendor SDK, run latency and reliability tests, evaluate admin features.

Compare based on measured data, not assumptions.

Buy-to-build strategy

One pragmatic approach many leaders use:

- Start by buying to gain speed and mitigate early delivery risks.

- Plan to build later once usage patterns, edge cases, and economics justify deeper investment.

This hybrid strategy strikes a balance between avoiding premature optimization and maintaining long-term flexibility.

Case studies

Abstract principles become concrete when applied to real systems. Here are three domains where engineering teams consistently face build vs buy decisions, with clear decision criteria:

Authentication and authorization

When to buy (90% of cases)

- Your app needs login, user roles, and basic permissions

- You want proven security without becoming a security expert

- Compliance requirements matter to your business

- Examples: Auth0, Okta, AWS Cognito

These services have solved the hard problems that would take your team months to implement safely.

When to build (rare exceptions)

- Identity management IS your core product (you're building the next Auth0)

- Extreme data sovereignty requirements (government, healthcare in certain regions)

- Your authentication flow is so unique that existing services can't support it

- Reality check: Even large companies like Airbnb and Slack buy authentication services

Billing and payments

When to buy (95% of cases)

- You need to charge customers money (shocking, I know)

- Global payments, tax compliance, or subscription management required

- You want to launch in weeks, not years

- Examples: Stripe, Paddle, Chargebee

- Payment processing involves banks, regulations, and fraud detection that would cost millions to build from scratch.

When to build (only at massive scale)

- You process billions in transactions where 2.9% fees become material (think PayPal, Square)

- Your payment flow is deeply integrated into a complex financial product

- You have dedicated compliance and fraud teams already

- Reality check: Even billion-dollar companies like Shopify started with Stripe and only built payments after massive scale

Notice the pattern: Buy when it's a commodity supporting your business. Build when it's core to your competitive advantage. Most teams overestimate the uniqueness of their needs and underestimate the hidden complexity of seemingly simple systems.

Conclusion

For tech leads, the 'build vs. buy' decision is less about the technology itself and more about what the decision enables. Building can give you differentiation, control, and deep expertise, but it also ties your team to long-term maintenance and compliance burdens. Buying can accelerate delivery and reduce risk, but it may expose you to lock-in, pricing cliffs, and roadmap mismatches.

The best leaders don’t treat this as a binary question. They apply structured evaluation, run experiments, and utilize evidence-driven frameworks, such as weighted scorecards, spikes, and ADRs, to capture the rationale. They also recognize that a buy-to-build strategy, starting with a vendor for speed, then replacing it when scale or uniqueness demands it.

At the end of the day, your job as a tech lead isn’t to always choose the “right” path in hindsight. It’s to make the tradeoffs explicit, defensible, and aligned with company strategy. If you do that, whether you build or buy, your team will have clarity. That clarity is what keeps velocity and trust high.

Was this article helpful?

Find your next developer within days, not months

In a short 25-minute call, we would like to:

- Understand your development needs

- Explain our process to match you with qualified, vetted developers from our network

- You are presented the right candidates 2 days in average after we talk